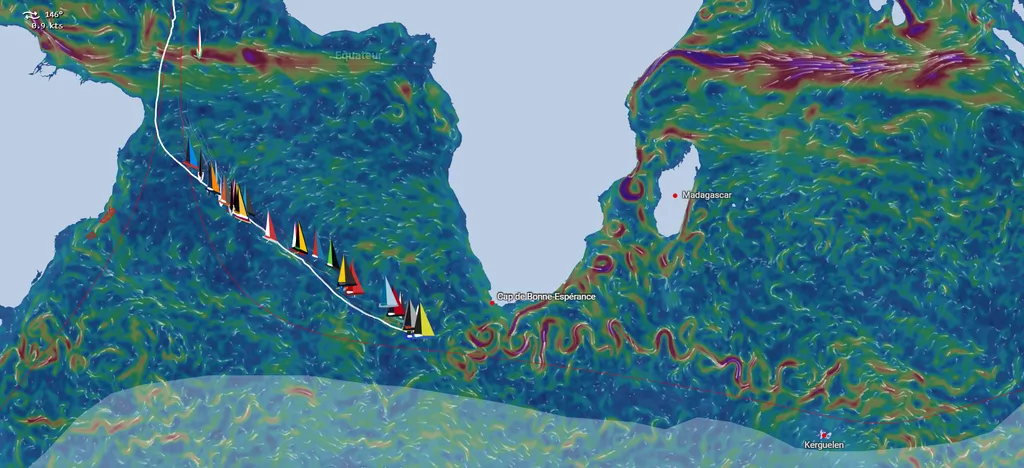

The Agulhas Current runs along the East African coast descending after Madagascar and running along the Mozambique Channel. And just before the Cape of Good Hope, it diverges from the coast and then makes a 180-degree turn, a big reversal off the tip of the African continent. At this point, it generates whirlpools with very strong currents (up to 2.5 knots). These are the rings of the Agulhas Current, well known to sailors.

The Vendée Globe sailors pass far from the Cape of Good Hope, much further south where they catch the edge of the reversal of the Agulhas Current to be helped on their way eastwards.

But it is an important current in terms of biodiversity. The water is marked by horizontal movements on the surface but also by vertical movements that promote life below the surface. Indeed, whirlpools bring nutrients, present in deep and opaque waters, to the surface where light promotes the growth of plankton, the first link in the trophic (food) chain. In addition, whirlpools also carry floating waste.

Sensors, satellites and digital models help us understand ocean currents

The oceans are in motion. The wind generates waves, the Moon and the Sun cause the tides, the rotation of the Earth generates whirlpools. And to add the vertical dimension, cold and salty water sinks. A vast oceanic conveyor belt thus transports each drop of water around the world, from the surface to the bottom and from the bottom to the surface. Clément Vic tells us more about the scientific questions he still asks about this mechanics of currents: