How is time measured on board?

"On board, time on land is no longer correlated with the rest of the world," explains Éric Bellion. The skipper of Stand As One, who has already competed in one Vendée Globe (2016-2017), says that time "becomes a scale, a gradation, a way of separating tasks". In fact, he only wears a watch at sea. It keeps track of how much sleep you get, how much time you spend manoeuvring and how much time you spend at the helm, but that's not all. "The day is also punctuated by the weather files and rankings that we can download at regular intervals," confides Romain Attanasio (Best Western-Fortinet).

To achieve this, the sailors don't use French time, but Universal Time Coordinated (UTC), commonly known as UT time. "We live in universal time, we sleep in universal time, we talk in universal time," smiles Éric. "UT time is our unit of time", agrees Romain. Winter time in France is UTC+1 (one hour ahead), and summer time is UTC+2.

How do you deal with the time difference on board?

When crossing the world's seas, sailors pass through several time zones, to the point of being completely out of sync with French time. And that's one of the reasons why UTC time is particularly valuable. "At the start of the circumnavigation, when the sailors head down the Atlantic and round the St Helena high, they don't cross any time zones," explains Romain. "On the other hand, as soon as you start heading east, the time zones change". As a result, he admits that measuring time is "sometimes confusing". "I try to keep to an earthly rhythm, with breakfast, lunch and dinner during the day, but it's not easy. Sometimes you get lost and you know you also have to be careful not to wake everyone on land!"

In the Pacific, they also have to cross the anti-meridian, which is a real brain-twister. This is the meridian opposite Greenwich, 12 hours away. This longitude, also known as the 180th meridian, corresponds to the date line. When Charlie Dalin crossed it in the last Vendée Globe, he was the race leader at the time, and he was amused: "It's my second Sunday in a row, but for me, Sunday or Monday, it doesn't make any difference!"

Day or night, what difference does it make?

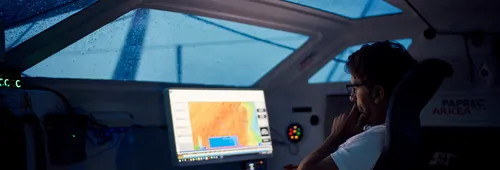

One thing is certain: at night, "everything is harder", says Romain. "Before nightfall, you prepare your equipment, your headlight and your helmet," explains the sailor from Fortinet-Best Western. You're more tired, you can't see properly and you know it's going to be more complicated. This forces you to be more attentive, vigilant and concentrated, which increases fatigue... and can give the impression that time is passing slower. "There's always a little twinge of guilt when the night comes. You know you're going to be under more stress, going into the dark," continues Éric. "It's dangerous at night. But as soon as you get out of it, the light comes back on and that's a comfort, a boost of enthusiasm". The sailor on Stand As One adds: "I've learnt that you lose a month of your life for every sleepless night... That means I've lost a lot!"

More generally, what is the perception of time on board?

Éric Bellion assures us that after several weeks at sea, "the idea you have of a day ashore disappears like sand between your fingers". Being constantly focused on your machine ends up blurring your reference points. "Our big markers are nightfall and sunrise," explains Romain. The skipper, who is about to take part in his 3rd Vendée Globe, admits that the difficulties on board can "sometimes give the impression that it's long and interminable".

On the other hand, as soon as everything is running smoothly - the boat, the trimming, the conditions - time seems to fly by more quickly and also seems to be conducive to "a few moments of daydreaming that someone on land doesn't allow himself as much as a sailor", says Éric. In more general terms, he asserts that at sea "everything is more intense": "it's a curse, especially for our loved ones because it's not easy to grasp sometimes. However, at sea, happiness is even happier and misfortune even more unfortunate."

How do you readjust to the time on land when you arrive?

Readjusting to everyday life, to family and friends, to the little obligations of everyday life... And to the rhythm of the land. The stakes are high when you return from nearly three months alone at sea. And there's nothing easy about that. "The fatigue can last for a long time. You're not just burnt out by the race, but by all the preparation that goes into it, which lasts several years." Romain Attanasio is no different: "at the end of my first Vendée Globe, it took me 2 and a half months to sleep through the night. After my 2nd Vendée Globe, I never managed to do it again." The skipper of Fortinet-Best Western remembers meeting a man who had worked nights for 15 years: "He had never managed to sleep through the night and sleep normally again." Sometimes, even on land, the way time passes seems decidedly interminable.